To close out our series on “Slargon” we focus on the importance of plain language in climate change communication.

Experts say that communication is key to a healthy relationship. Psychologists talk about communication in marriage and managers talk about communication in business. Susan Joy Hassol, a climate change communicator, analyst, and author with the non-profit Climate Communication, knows communication is key to spreading information about climate science. Susan was the Senior Science Writer on all three National Climate Assessments, authoritative reports written in plain language to better inform policymakers and the public about climate change and its effects on our nation. She has also written for a climate change documentary on HBO. Her ability to write and present information shows that you have to be more than a good scientist – you have to be an effective communicator. It is our pleasure to speak with her about communication in climate change.

_______

How did you first get involved in climate change communications?

My work in the energy arena and at the Aspen Global Change Institute brought me to believe that climate change was the greatest challenge and opportunity facing humanity today. At the same time, I realized that I seem to have the ability to translate science into language that lay people will understand and care about. So I figured the best use of that talent was to apply it to the most important issue of our time. I’ve now been doing this for more than 25 years. Among other things, I’ve been the writer on all three U.S. National Climate Assessments, testified before Congress, written an HBO documentary, been on national television and radio, provided communication training and support for numerous climate scientists, and spoken to many influential groups. More on my efforts can be found at my website, climatecommunication.org

What do you think is the most pressing issue with communicating  climate change today?

climate change today?

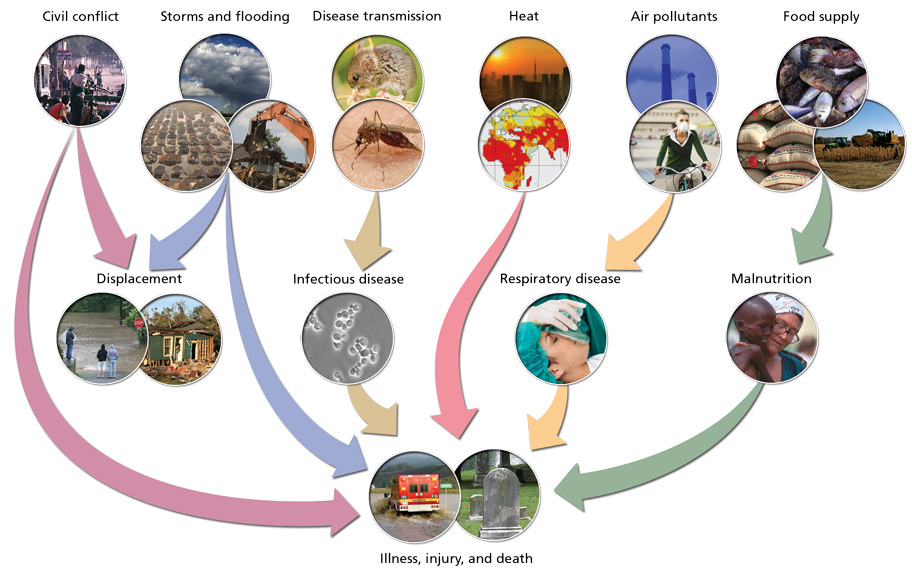

One of the most pressing issues is overcoming the ideological divide that causes some people to resist the actions needed to reduce emissions and limit climate change. A big part of this problem is that special interests that benefit from the status quo actively support a disinformation campaign that seeks to cast doubt on the science, just as they did in the tobacco wars when it became clear that smoking was a cause of cancer. Another pressing issue is to communicate the urgency with which we must tackle climate change if we are to avoid catastrophic effects. We need to cut emissions as much as we can, as fast as we can. Fortunately, the technologies needed to do this exist and have a wide array of benefits for our health, security, and economy. We just need to put effective policies in place to scale these technologies up even more rapidly than is occurring now.

You also wrote a documentary for HBO about climate change called “Too Hot Not to Handle” in 2006. Tell us a little bit about that experience.

What was really important to me in writing that documentary was to focus on the impacts we’re experiencing now in our own backyards, and to devote half the film to solutions that Americans are pursuing now. Both of these things help bring the  issue home for people. I also wanted to put the faces and voices of my scientist colleagues in front of our viewers so they could hear about climate change right from the horse’s mouth. There was no narrator, no disembodied voice of the network heard so often in documentaries.

issue home for people. I also wanted to put the faces and voices of my scientist colleagues in front of our viewers so they could hear about climate change right from the horse’s mouth. There was no narrator, no disembodied voice of the network heard so often in documentaries.

How do you help scientists improve how they communicate with the public?

I’ve given many talks and workshops for scientists to help them become more conscious of the problems with how they communicate and to learn the techniques of doing it more effectively. This ranges from connecting on values and establishing trust, to avoiding jargon and words that mean different things to the public, to establishing more of a dialog and less of a lecture. I’ve taught them to anticipate the public’s misconceptions, and how they can make themselves more human and accessible and less intimidating. I’ve also worked one-on-one with many scientists to help them refine their writing and speaking, such as when they’re preparing to give Congressional testimony. I’ve used videotapes of the good, the bad, and the ugly in science communication to help them see what works and what doesn’t. And I give them lots of opportunities to practice and receive feedback. I’ve seen great improvement and a lot more interest among scientists in learning how to communicate well.

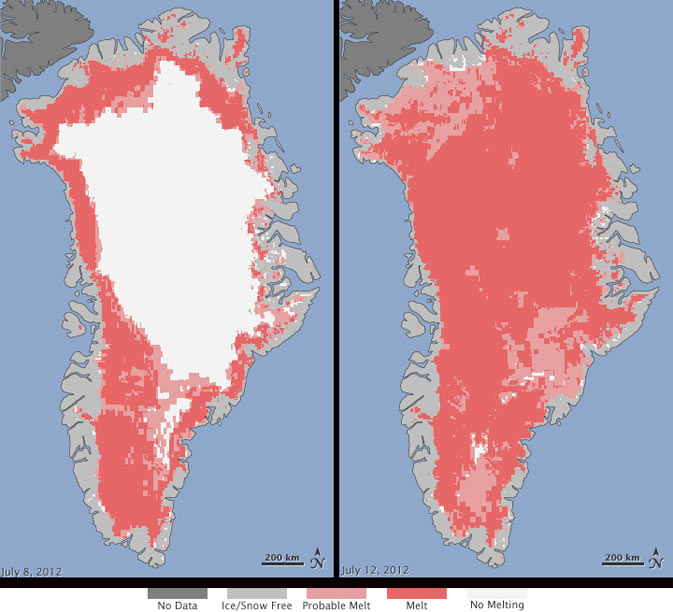

Extent of surface melt over Greenland’s ice sheet on July 8 (left) and July 12 (right) 2012. Measurements from three satellites showed that on July 8, about 40 percent of the ice sheet had undergone thawing at or near the surface.

You have worked on major projects that have been in the spotlight for years. How do you see the tide turning when it comes to communicating about climate change?

I think we’ve laid the groundwork by clearly showing that climate is changing, that humans are causing it, that scientists agree on the basic science and cause, and that the effects are apparent now and will grow much worse unless we change our emissions trajectory. What I see turning the tide is that the solutions are available now and make great sense economically. A much greater focus of communication should be on speeding the transition from the dirty energy system of the past to a clean, renewable energy future.

What can climate change communicators do to improve their message and increase public understanding?

Talk to people about values we all share. No one wants more killer heat waves, floods, and insect-borne diseases. We don’t want to leave our kids with a problem they can’t solve. Talk about impacts that are close to home; the polar bear is not the best symbol of climate change when people are feeling its effects in their own backyards. And place the greatest emphasis on solutions. Everyone wants a clean, healthy, prosperous future. Renewable energy is increasing rapidly in many places, but it’s not happening fast enough. We need policies in place that speed this transition because we have just enough time to avoid the worst if we do as much as we can as fast as we can.

Do you have any referrals for more information, or any other ideas you can share?

Our website climatecommunication.org has a wealth of information, so I’d point people there as a good place to start. For example, our Resources section links to videos, articles, other websites, and more. Our narrated animations provide a quick way to learn about the science and share the information with others.

Recent Comments