Time for another installment in our ongoing “Slargon” series!

The contest about whether human-made climate change is happening is over. Climate change won. Now the contest is whether we can adapt, reduce, and clean-up fast enough. With that contest comes a new era of legal battles over what individuals and companies are responsible for adapting to. It is these legal battles where specific use of terminology makes all the difference in how a policy is enacted.

Tim Duane, a professor of law and a consultant to the renewable energy industry, spoke to us about the importance of language and avoiding slargon in creating sound policy for the future. Slang or jargon can muddle technical policy and create loopholes in laws, a key tactic for climate science deniers in legislative positions. Even small differences in terminology – “may” instead of “shall” – can water down regulations and stymie enforcement efforts. We are happy to have him share his perspective with us.

_______________

Please tell us a little bit about your background in law and how you came to specialize in environmental law and energy policy.

I first became involved in the renewable energy industry in the late 1970s when I was an undergrad at Stanford University. I worked with solar energy developers, municipalities, and then joined the alternative energy section at PG&E when I finished my master’s degree in Civil Engineering. Ultimately, I started a consulting business, worked with the largest renewable energy companies in the world, completed my Ph.D. at Stanford and joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley to teach environmental planning and policy. Engineering, economics, and ecology are all central to dealing with modern energy and environmental problems—but we also need to address legal institutions to implement effective policy. So I completed my J.D. at Boalt Hall after I got tenure at Berkeley and I now split my time between the University of California, Santa Cruz (where I’m Professor of Environmental Studies) and the University of San Diego School of Law (where I am a Visiting Professor). I am also a licensed attorney and consultant who advises both private and public clients on policy and projects.

How has communicating environmental law changed your understanding of climate change?

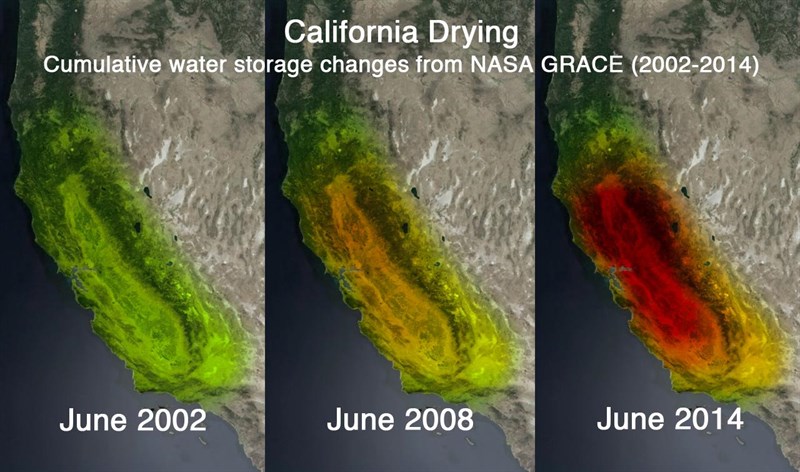

I first wrote about climate change in 1990, so this is not a new issue for me. But climate change and environmental law are still just getting to know each other—and that means there is both tremendous uncertainty about the field and enormous opportunity to influence its future. That makes it an exciting topic to teach and to advise clients and policy-makers on. Our language has evolved, though, from “global warming” to “climate change.” Neither of those terms begins to capture the range of probable impacts from greenhouse gas emissions on the planet, though; instead, “climate disruption” is a much better term. “Abnormal is the new normal,” as we have seen with California’s drought and fire regimes—so we need to shift how our society handles a much higher level of risk and uncertainty. Legal regimes, though, are built to provide stability.

How do you think the legal industry can improve communications about climate change so policymakers and the public can have a better understanding?

The shift from “climate change” to “climate disruption” makes uncertainty and instability more important in how we think about how to manage risk. Both the broader public and my clients want to reduce risk and uncertainty, so we need to innovate with new legal tools to hedge that risk. Financial markets have created such tools, for example, and there are ways for both farmers and airlines to hedge their risk of volatile commodity prices or jet fuel prices. We need to develop similar legal mechanisms for water users and energy consumers and wildlife conservation. Building in adaptability—together with science-based and market-based information on both what is happening to the environment physically and how those changes are affecting social and economic value—is our biggest challenge as a society. And California water management is at the forefront of translating the abstract problem of climate change into real-world legal conflicts. We need to move beyond the current “zero-sum” framing of the water crisis in California: the entire system needs to be modified to reallocate both risk and reward to improve water management. That will require some fundamental changes to many of our legal institutions around water.

What are some examples of a particular word changing policy or legislation?

Much of modern climate and environmental law is “statutory,” meaning it is based on statutes adopted by a legislature that reflects a political compromise over the specific words to deploy. I teach my students to go through the text of a statute—or a regulation, adopted by an agency to implement the statute—with a highlighter to make note of key words like “shall” or “may.” Often, that one word choice will determine whether or not an agency can be compelled by a court to do something. “Shall” makes it clear to the court that the agency needs to do something; “may” gives the agency enormous discretion in how the agency implements the legislature’s intentions. So I would say that the “shall/may” difference is the key to substantive policy in most legislation.

United States President Barack Obama addresses the Climate Summit at United Nations headquarters, September 23, 2014. (AP Photo)

What communication strategies work best to deliver information about climate change? How have you seen particular words used to downplay climate change or reduce accountability?

I was the keynote speaker in 2004 for the Western Climate Science Symposium, which had over 100 top scientists working on climate change research. I was basically asked to address the question of why their science didn’t seem to be influencing policy. I read through many of the terrifying science papers they had published and found that the science just wasn’t being presented in a narrative that was accessible to most people. Saying that “median snow storage in the Sierra Nevada across the 14 model scenarios was reduced by 48.2% with a standard deviation of 5.7% by the year 2078” was too complicated and abstract for most people. I translated that study and another one into a more compelling image: “By the time my grandchildren are my age, we’ll have half the snowpack and twice the fire in the Sierra Nevada.” This is an image we can imagine—we’ve seen grandchildren, snow, and fire and have a sense of how those three things go together to describe a future that is not from Star Wars or Star Trek. Today, we have already seen that projection from the models realized on the ground—in the snowpack and fires that are burning right now. So that future is even easier to visualize now.

What words are you hearing most often? What words are fading out?

Among scientists and policy-makers, “climate disruption” is taking hold—but it hasn’t been picked up yet by the media. I think there are good reasons that existing fossil-fuel producers would like to keep the discourse at the more soothing level of “climate change.” But the erratic and historically unprecedented changes we are experiencing make most people talk casually about how the weather is “weird” or “strange” compared to the past. So “climate disruption” may take hold—it really does mean you can have both hotter and colder conditions at the same time. A drought in the west is consistent with more intense winters as greater heat in the system drives greater moisture in the air and the jet stream shifts as regional differences play out.

Cumulative water storage changes between 2002 and 2014. Decreasing water storage results in increased fires and less containment. Source: Capital Public Radio)

How has the language of energy policies shifted in regards to climate change over the last few decades? How about in the last few years?

Climate denial has taken a new form: previously, it was a claim that “the jury is still out” on whether climate has and is changing; now, it is the claim “I’m not a scientist” and that any changing climate is a natural phenomenon that can’t be traced to human activities (with a reprise of “the jury is still out” on that question). But the jury isn’t still out: it’s a nearly unanimous verdict among qualified scientists. Moreover, phrases like “clean coal” and “the war on coal” simply deflect attention from the actual factors driving the rapid collapse of the coal industry. Pushing for a shift to natural gas fails to account for the global warming potential of methane, which is emitted in the life cycle of producing natural gas (accounting for it makes “fracked” natural gas roughly as bad as coal for producing electricity on a life-cycle basis). An “all of the above” energy strategy may play well with key campaign contributors, but it obscures the need to make strategic investments to transform our entire economy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We therefore need to focus more on the enormous technological and business opportunities we have through investments in energy efficiency, renewable sources of power, and alternative transportation fuels rather than continue to invest in obsolete energy sources that will simply delay a necessary transformation—while making climate disruption worse.

What research are you currently working on?

I’m very excited to be working on a project with a crack team of sophisticated, experienced modelers and researchers to develop a Blueprint for a Clean Energy Economy for the US by 2050. The project is designed to reach out to American business leaders and those who want to make America a leader in the global transformation that needs to take place over the next decade or so to reach the scientific consensus on emissions reductions: reducing US greenhouse gas emissions by roughly 80%. This is both possible and profitable if we put the right policies in place. I’m also working on the many near-term challenges that my clients face in navigating both state and federal laws and policies—and the impact of climate disruption—on their businesses.

—————

You can hear a recent interview Tim Duane did with the Institute of the Americas about energy policy and climate change at https://www.iamericas.org/en/ioa-programs/energy1

Recent Comments