If you’ve been waiting for the answer to last week’s riddle, the time has come. What is east and royal and tidal all over? The King Tides Trail, of course!

The American playwright Wilson Mizner famously said, “Art is science made clear.” There may be nothing that captures this sentiment for the science of climate change as accurately as the King Tides Trail project in Portland, Maine. Created by Jan Piribeck, an Associate Professor of Art at the University of Southern Maine, the King Tides Trail project is an interactive art piece that wraps 4 miles around the Portland peninsula and uses markers and geographic data points to show the anticipated impacts to the city from a changing climate. The project identifies areas that would be flooded by rising tides in the next 50-100 years and illustrates this hard-to-grasp concept of sea level change in a visually clear way.

Today Jan speaks to us about her work on the King Tides Trail project. For over a decade Jan has focused her work on a series of projects that fuse Art and Geographic Information Systems. Jan and her team unveiled the King Tides Trail Project on December 8, 2014. The project is meant to inspire awareness about the impacts of climate change to the Portland community as well as the rest of the world. We welcome her insights about visual communications for climate change issues.

– – – – – – – –

Who first came up with the idea?

The idea came from the process of observing high tides and their impact on my neighborhood in Portland, Maine. I live in part of the city that just a little over a century ago was covered by waters from the Back Cove, a mile-wide tidal basin located nearby. About five years ago I began noticing areas that flooded regularly during high, high tides. At first I thought this was rainwater, but upon further investigation found it to be brackish water that pushes its way up through storm drains. I decided to start working with students at the University of Southern Maine (USM) to observe and record these tidal inundations, which led to a study of sea level change. Living on a peninsula offered the opportunity to observe a number of sites that are vulnerable to rising tides. Many of these are located along two popular cycling/walking trails in Portland, and it made sense to mark these sites and create a pathway around the shoreline of the city for those who want to witness the impacts of the highest tides of the year, also known as King Tides.

How many people were involved?

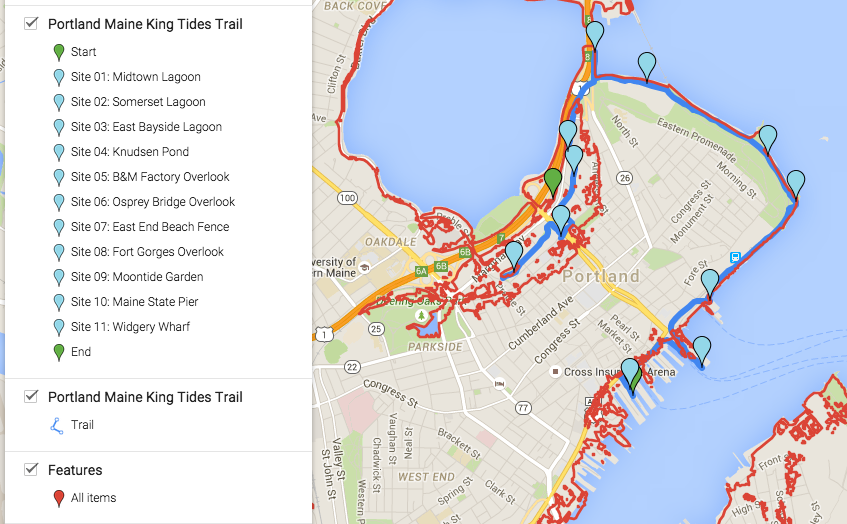

A core group of 15 students was involved in creating a temporary installation marking the location of a 3’ sea level line and the King Tides Trail. The students also created a Google Map of the trail showing points of interest and the trail’s proximity to the 3’ sea level line.

The following students gave generously of their time, energy and talent to the development of the Portland King Tides Trail: Nicholas Barter, Nathan Broaddus, Amber Desrosiers, Marina Douglas, William Freeman, Ken Gross, Emma Hazzard, Richard Hudon, Abigail Johnson-Ruscansky, Ryan Jordan, Kristyn Peterson, Caitlin Puchalski, Samantha Quimby, Lisa Willey, Mike Witherell

Vinton Valentine, Director of the USM/GIS Lab and Marina Schauffler of the Gulf of Maine (GOM) King Tides Project provided valuable assistance throughout the project.

What was your role?

I was the project director; this involved organizing and presenting lectures to orient the students to data about sea level rise (SLR) and to various forms of installation art. I facilitated discussions and activities leading to the design and implementation of the King Tides Trail and was the liaison with the city of Portland and the GOM Council and King Tides Project.

The project seems like a great way to help the public visualize the impacts of rising sea levels. Please explain the method you used in this project.

We used over 2,000 red surveying whiskers pounded into the ground with 60-penny nails to delineate and make visible a portion of the 3’ SLR line. The space we marked is located in an empty urban lot slated for real estate development. We used GIS (Geographic Information System) mapping tools to project the line, and loaded this data into a hand-held GPS (Geographic Positioning System) receiver. This enabled us to walk and mark the line in physical space. We also used GIS to map locations for 28 Beacons (blue wooden stakes topped with solar lamps) along the King Tides Trail. The Beacons marked the trail and sites along the trail where tidal changes can be easily observed. Additionally, circular sidewalk graphics were created to mark locations vulnerable to flooding. Some of the sites were given names such as Knudsen Pond and Somerset Lagoon as a way to form a narrative around SLR in Portland. Hand-painted maps have been created to document the whereabouts of these locations.

Do you have other ideas for how to visualize rising sea level?

Yes. Each student came up with a proposal for an installation. We couldn’t create them all, but they were all compelling. For example, one student proposed compacting trash collected from beaches to make large sculptural cubes that could be used to construct sea walls. The absurdity of the idea is part of its strength. These sea walls wouldn’t be functional except to point out the excessive waste that is contributing to the demise of our atmosphere and in turn leading to accelerated sea level change. All of the students were inspired by Tsunami markers, which are stone slabs used to mark where Tsunami waves have occurred. The markers warn against building on these spots. Another student proposed a large-scale cast concrete sculpture inscribed with wave patterns to be installed at the portal of the King Tides Trail. There were many more ideas that deserve future consideration.

How did your team decide on this method?

We wanted to do something where the entire class could be engaged in the making, and we had several factors such as durability and visibility that factored into the decision to use the marking whiskers, stakes and sidewalk graphics. Due to the collaborative nature of the project, students wanted to pick materials that were representative of the entire group and not reflective of just one aesthetic voice. The materials chosen borrowed from the visual vocabulary of surveying tools, which went along with the idea of the students being environmental and cultural surveyors and workers. We wore hard hats with HAT (highest annual tide) at the work site.

Have any other coastal cities in the U.S. undertaken this type of art project.

Volunteers installing red whiskers along Portland high tide line during an early stage of the project. Source: University of Southern Maine.

There is a really interesting project called HIGHWATERLINE that does workshops and public art to mobilize communities to develop resiliency to climate change. They do work in cities throughout the country.

Did you need permission from the City of Portland for your project?

Yes!

If so, how easy/hard was it?

The city of Portland was supportive, but there were protocols that took time to work through. This involved things like dig safe permits and approvals by the Portland Public Art student art review committee. The class made a formal proposal that outlined materials, maintenance and dismantling plans and so on. Everything had to be approved before final permits were issued.

Were there any particularly challenging obstacles?

We were working under a compressed timeframe and the protocols seemed prohibitive at times, but in the end the cooperative and flexible attitudes of the city officials and persistence on our part helped assure that the project would happen.

You received funding through the Limulus Fund at the Maine Community Foundation. How did you go about pitching this idea to the foundation?

The grant was submitted through the Gulf of Maine Council on the Maine Environmental Climate Network. They did the pitch and were successful.

How competitive was the process?

I’m not sure, but I think the review is quite thorough. Proposals have to show merit and be viable for completion.

How has the public reacted to the project? What have been some of the most interesting responses?

There was interest on the part of the media. The project was covered well in local newspapers and was featured on Maine Public Radio. Many people reached out to tell me they enjoyed reading and hearing about the project, and those who jog along the King Tides Trail have mentioned seeing the glowing Beacons at dusk.

Do you think the project will prompt the city to take action to mitigate against the rising sea levels?

The scenario of a 3’ rise is more severe than what the city is officially planning for. The apartment complex to be developed in the empty lot where we marked the 3’ SLR line has been approved, and there are plans to elevate the surrounding roads by 2’ to accommodate rising tides. This is in accordance with current flood maps; however, the question intimated by the King Tides Trail is, will this be enough? The installation was informed by the research of Maine State Geologist Peter Slovinsky, who points out that the latest scientific predictions for SLR are 1’ by 2050, 2’-3’ but potentially more by 2100. The State of Maine has adopted 2’ as a middle-of-the-road prediction by the year 2100 for areas with regulated Coastal sand Dunes. Slovinsky suggests examining scenarios of 1’, 2’, 3.3’ and 6’ on top of the highest annual tide. These scenarios relate to the National Climate Assessment, and also correspond well with evaluating potential impacts from storm surges that may coincide with higher tides today. The aim of the King Tides Trail was to illuminate these potential impacts through artistic visualizations and processes.

The city is aware of the work we did, but there is no indication that the project resulted in specific action. Information about the trail will continue to be distributed through a website and digital database that are due for publication this week! Communication and collaboration with the city to raise awareness of SLR was one of the goals of the King Tides Trail, and headway was made in this regard.

How would downtown Portland be impacted if sea levels did, in fact, rise three feet by 2100?

There would be a dramatic impact on waterfront properties and on some locations that are currently not considered to be waterfront properties. One of these would be the parking lot in front of my condominium; I live not far from the downtown, and my parking spot would be under water given a 3’ rise.

Red whiskers placed in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood identify where the tide line would be if sea level rose by three feet. Source: The Forecaster

What are some things the city can start doing today to prepare?

About a year and a half ago the Portland Society for Architecture hosted a symposium called Waterfront Visions 2050. They brought in experts on sea level adaptation to address concerns about Commercial Street in Portland’s Old Port district. It was an incredible program that included an exhibition and public forum for sharing ideas about what to do to prepare. There are many innovative ways to address SLR. The important thing is not to ignore that it is happening and not to panic and make unwarranted choices about vacating properties.

Have you thought about doing a similar King Tides-type project in another coastal area? Or whatever other projects are you pursuing at this time?

There is great potential to expand the King Tides Trail beyond the Portland peninsula. This summer I will focus my energies on extending the project into Casco Bay. Ideally, I would like to travel to coastal communities throughout the Gulf of Maine and along the US coastline to do similar projects.

– – – – – – – –

To learn more about the King Tides Trail project, visit https://esealevelchange.org/. You can also learn more about “Envisioning Change,” an art collaboration in Casco Bay to visualize climate change impacts, of which the King Tides Trail project was a part, by visiting the University of Southern Maine Digital Humanities program at https://usm.maine.edu/usmdh.

Recent Comments