The self-anchored suspension tower as seen from the original Bay Bridge East Span.

(Photo courtesy of Tom Paiva/BATA)

The San Francisco Bay area has another impressive icon to add to its skyline. The East Span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge officially opened to traffic Labor Day weekend. After 11 years of around-the-clock construction, the previous cantilever portion of the bridge has been replaced with a new self- anchored suspension bridge and two parallel roadways with five lanes in each direction. At 2,047 feet long with a single 525-foot tall tower, the East Span’s self-anchored suspension bridge is the world’s largest. The bold beauty of the self-anchored suspension bridge’s graceful asymmetric design is not only aesthetically pleasing, it can absorb most of the shock from an earthquake to prevent damage to the main structure.

The original San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. While the bridge was repaired and opened to traffic one month later, it was determined that the best solution in the long-term would be to retrofit the West Span and replace the East Span.

Opening the bridge to traffic, complete with a traditional chain-cutting ceremony to mark the milestone, seemed fitting for Labor Day weekend after the decades of design and construction work done on the six seismic safety projects that make up the bridge. While traffic is now flowing there is still some work left to do before all components of the new and improved bridge, including a pedestrian and bike path, are in place.

State and local officials join California Lt. Governor Gavin Newsom to open the East Span by re-enacting the chain cutting that marked the opening of the original Bay Bridge in 1936.

(Photo courtesy of Caltrans)

As Collaborative Services continues its celebration of Labor Day all month long through our exploration of BIG projects we could think of no better BIG project to feature than one that’s opening coincided with the holiday. We talked to San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge spokesperson, Andrew Gordon to learn about the challenges the project faced along the way, the bridge’s unique design, how the public was kept informed, and what work is left to be completed.

– – –

Like many large public works projects the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge has found itself tied up in political battles, cost overruns, and engineering challenges. How did the project overcome these challenges and stay the course?

Building the new East Span has been a monumental endeavor, in terms of both the hurdles we have overcome and the feats that we have accomplished. The new East Span has been in the works since the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, when a 250-ton section of the original East Span’s upper deck collapsed, killing one motorist. Since then, the new bridge has been subjected to political battles, cost increases due to design changes and material cost, and unforeseen construction challenges. The project has overcome adversity by never forgetting the job at hand – building a structure that carries Bay Area traffic safely.

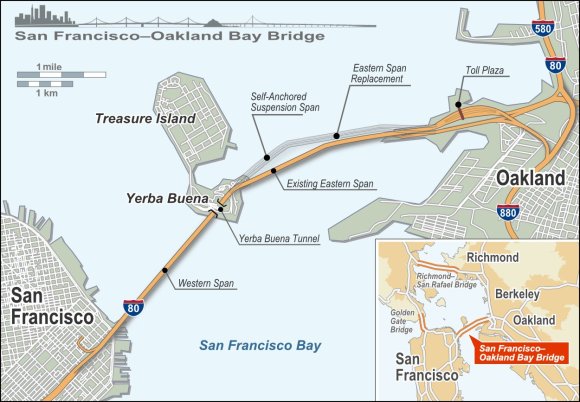

A diagram of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Seismic Safety Safety Projects.

(Credit: The San Francisco Citizen)

In July 2005, the Toll Bridge Program Oversight Committee, consisting of the California Department of Transportation, the California Transportation Commission and the Bay Area Toll Authority was formed to oversee the Toll Bridge Program, and to improve accountability and ensure openness. Since the creation of this committee, the project has remained on-budget and on-schedule.

After 32 bolts broke on one of the bridge piers in March, we rose to the challenge by bringing the best and brightest engineers and designers together with an outside panel of experts and the Federal Highway Administration. This combination of internal and external collaboration ensured that our retrofit solution was the best possible.

Contractors, engineers, consultants, renowned experts and architects have worked together to push the limits of design and engineering to create one of the most seismically advanced structures in the world.

At 2,047 feet long, the new east span is the largest self-anchored suspension bridge structure in the world. Why was a self-anchored suspension design chosen for this bridge?

Discussion about the new bridge design began in 1997, when Bay Area elected officials and the public decided they wanted a bridge that was both seismically sound and aesthetically appealing. In March of 1997 the Metropolitan Transportation Commission appointed the Bay Bridge Design Task Force to forge a regional consensus on the design of the new East Span. A single-tower self-anchored suspension (SAS) bridge design with a pedestrian and bike path on the south side was eventually selected in 1998. This design was chosen for a variety of factors. Architecturally, it reflects the Bay Area’s strong tradition of suspension bridges, including the Golden Gate, Bay Bridge West Span and Carquinez Bridge. It also corresponds with the geologic constraints of the region. The tower foundations sit deep within the last remaining portion of bedrock before the Oakland shoreline, providing structural stability as well as a dynamic, asymmetric appearance. The Self-Anchored Suspension span has been designed to be aesthetically unique as well as functional— an iconic landmark capable of withstanding a major earthquake.

State of the art LED lights illuminate the self-anchored suspension span.

(Photo courtesy of Tom Paiva/BATA)

The bridge’s new east span was designed and constructed to withstand the strongest possible earthquake that may occur within the next 1,500 year period. What are some of the cutting-edge innovations and enhancements that were used to achieve this?

The new bridge was designed to meet the most stringent earthquake standards and to act as a regional lifeline structure, opening to traffic within a day or two after the strongest ground motions expected in a 1,500-year period. Since 2002, the design, engineering and construction teams have met the challenge of making the new East Span seismically resilient with groundbreaking technology and enhancements – some never before used in bridge building – that have transformed the bridge into a state-of-the-art engineering marvel.

Numerous innovations help make the bridge secure, yet flexible enough to withstand the greatest seismic forces. The Skyway’s concrete deck sections sit on 160 rebar and concrete steel piles driven at an angle up to 300 feet below the water’s surface, through a process called “battering.” While this method has been used to secure foundations for oil rigs, this is the first time it has been used for bridge construction. The hinge pipe beams that sit between the roadway sections act like giant shock absorbers, designed to move within their sleeves during expansion or contraction of the road decks during minor events. They are also designed to absorb the energy of an earthquake by deforming in their middle or “fuse” section, which will minimize damage to the bridge’s main structure. The single, 525-foot tall tower is made up of four separate pentagonal legs connected by shear link beams. These beams allow the legs to move independently, and are designed to protect the tower from catastrophic damage by absorbing seismic energy during an earthquake.

Much of the construction work done on this project was done during live traffic. What were some of the challenges this created and what unique approaches were used to ensure the safety of the traveling public and crew members during demolition and construction?

The bulk of construction work was done next to live traffic so there was little interference with the traffic flow on the original Bay Bridge.

During Labor Day Weekend 2009, crews faced the challenge of building the Yerba Buena Island Transition structure without disrupting the flow of traffic into the Yerba Buena Island Tunnel. To accomplish this daunting task, eastbound and westbound traffic were shifted off the original roadway onto a temporary detour. The new detour sat just south of the roadway, and allowed the contractor to demolish the original westbound approach to the tunnel and continue construction on the new transition structure.

Over Memorial Day weekend in 2011 and President’s Day weekend in 2012, crews realigned traffic lanes and built detours west of the Toll Plaza, allowing engineers and construction crews to complete the last eastbound section of the Oakland Touchdown sooner than expected. This detour allowed east and westbound traffic to start traveling on the new East Span at the same time.

What type of public involvement efforts were done throughout the project and how was the public kept informed during construction?

The new East Span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge has always been a source of public intrigue. When crews broke ground on the East Span in 2002, highly visible, large-scale construction endeavors began to capture the attention of the over 280,000 motorists who crossed the original span each day. As the Bay Bridge continued to grow and take shape, so too did public interest.

A Public Information Office (PIO) was established in 2005 by the Toll Bridge Program Oversight Committee with the goal of maintaining positive relationships, communication and outreach with the public and stakeholders to ensure smooth project implementation. The PIO serves as the nexus point for day-to-day communication and information for all stakeholders interested in the Bay Bridge.

The PIO facilitates weekly on-and off-site stakeholder tours, coordinates daily with local and regional media and supports third party documentary efforts from groups such as National Geographic, Discovery Channel and the BBC. Community relations have been at the heart of outreach efforts for the Bay Bridge, beginning with work done on the West Approach retrofit in San Francisco. The Community Relations team develops and implements a tailored outreach plan based on the varied constituencies and needs of the East Bay and San Francisco communities.

Our website, BayBridgeInfo.org, acts as a central hub for information about the project. Collateral materials, construction updates, lane closures and project photographs are all available to inform the public about significant impacts and project milestones. Social media has also become a fundamental outlet for us to disseminate information. We have developed unique content to inform our Facebook and Twitter users, and to drive traffic to our website.

The East Span of the bridge opened to the public this past Labor Day weekend and traffic is now flowing. What work is left to do to complete the project?

An inaugural procession of vehicles across the new bridge was part of the bridge’s grand opening event.

(Credit: The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge Seismic Safety Projects)

As soon as traffic was moved to the new East Span, crews began preliminary work to demolish the original span. Complete demolition will be divided into several parts: the cantilever/truss section, smaller truss sections, the S-curve and the foundations. The demolition process is expected to take about three years.

Work also remains on the bike and pedestrian path. Before the pathway can fully connect to Yerba Buena and Treasure Islands, crews will need to demolish a portion of the existing bridge that sits in the way of the new bike and pedestrian path in order to build and connect the rest of the path to Yerba Buena Island. The contractor will also construct a permanent connector to replace the temporary pathway from Oakland.

In August, crews successfully installed the temporary steel shims that allowed the bridge to achieve the seismic safety necessary to open to traffic. However, fabricators continue to work on the permanent steel saddle fix. The custom steel saddle system is designed to replace 32 broken bolts, providing an equal clamping force that will hold down seismic devices during an earthquake. The saddles are scheduled to be complete by December.

– – –

We look forward to crossing the new San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge one day whether by foot, bike, or motor vehicle. Best of the luck with the demolition and remaining work!

Liz Faris, Account Manager

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments