Do you text? Chances are you do. According to a 2012 Time Magazine article and Mobility Poll, 32% of people now prefer texting to making actual phone calls. But is the preference to text a good thing? Is it helping or hurting us, especially younger generations? By now most people are well versed in the acronyms used in texting. These acronyms have even morphed into somewhat of a language of their own. We live in a digital world where we are less concerned with the amount of words we use to communicate with and more concerned with the number of characters. This trend isn’t just for teenagers anymore, everyone from politicians to CEO’s to parents are embracing texting and its acronyms. But is our increased use of acronyms in texting threatening our literacy and spelling? Or is it causing the opposite effect? Will future generations be left lacking an understanding of the basic fundamentals of language? Or, as technology and language continue to evolve, will we soon be leaving the days of LOL behind for something new, saving the jobs of dictionary publishers and English teachers everywhere?

As we continue our exploration of slang, jargon and acronyms this month, we take a look at acronyms through the world of texting. This week Collaborative Services spoke with David Crystal, an acclaimed writer, editor, lecturer and broadcaster who currently holds the position of Honorary Professor of Linguistics at the University of Wales, Bangor. He has studied and written about text messaging, the use of acronyms in texting and its effect on society. Crystal spoke with us about why texting is criticized, whether or not it can help improve people’s literacy, whether the use of acronyms in texting is chalked up to just plain laziness, and maybe a prediction for the future of texting. We welcome his insights.

– – –

In your book Txtng the Gr8 Deb8, you state that sending text messages could improve people’s literacy because it provides more opportunity for people to engage with language through reading and writing. Do you apply this theory to children, as well?

That’s where the main evidence comes from, in fact. It was carried out on children. What you do is quantify in some way the amount of texting kids do, then give them some sort of literacy test (such as vocabulary awareness, or spelling ability) and look for a correlation. It’s quite tricky research to do, but several people have done it now, and the results are clear: the more you text, the better your literacy skills. People initially express surprise at this result, but upon reflection realise that it’s perfectly logical, because texting, as you say, provides practice, practice, practice. The pundits say ‘children don’t read these days’ – but have you ever seen a teenager NOT reading? The same pundits will say that they always have their faces buried in their mobile phones. So what do they think they are doing with these phones? Smelling them?

The other point to make is that the content of text messages is much more sophisticated than the pundits think. I often do school visits, and one of the things I do (or get the teachers to do) is make a collection of real-life texts, ready for analysis. They show very quickly how naive the pundits are. For example, a common remark is that text messages are short. But 160 characters, in English, allows 30 or more words. You can say quite a lot in 30 words, and some sentences are quite complex in structure as a result. The phenomenon of texting poetry illustrates just how much can be said in a short character-frame. Nothing new about this, of course. Think haiku.

You also tackled the notion of some pundits who say text messaging is destroying children’s ability to spell. You noted that texting abbreviations only make up around 10 percent of the content of text messages exchanged. You also note that abbreviations have always been part of the English language, so what do you believe causes this fear and criticism?

You’re thinking of people who present their vague impressions of how language works as if they were facts, and than try to impose their views on everyone else. Any linguistic novelty upsets them, and is used as evidence of a decline in language standards. There’s nothing new about this. Every new technology – printing, the telephone, broadcasting – has brought out the prophets of doom. The language, of course, goes on its normal healthy way, growing in expressive richness with each technological innovation. The nonsense that these pundits come out with is well illustrated by your comment ‘destroying children’s ability to spell’. The whole point of textese is that it relies on an ability to spell. If you can’t spell, you can’t text. And the best texters – such as the ones that go in for text competitions, or who write text-messaging poetry – turn out to be the best spellers.

When it comes to texting, what are some of the more creative or clever acronyms or abbreviations you’ve come across?

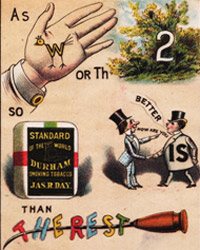

Actually, what struck me when texting abbreviations first arrived, was how familiar they all were. I don’t just mean familiar in Internet terms (for all the common ones were around on the Net, in chat rooms and the like, long before texting emerged). I mean familiar in English linguistic history. Abbreviations such as ‘c u l8r’ have been around for a very long time. Queen Victoria used to play rebus games using them. So did Lewis Carroll. And forms such as IOU go back centuries. So in fact there are very few genuine novelties in texting. But one thing IS novel. That is the way families of abbreviations evolve, such as IMO, IMHO, IMHBCO (‘in my humble but correct opinion’), and so on. I’d not seen anything like that before. But it’s more a playful exercise than a genuine communicative one. The longer (in terms of number of characters) the textism, the less likely it is to be used. Most of the abbreviations in the text-messaging dictionaries that have been compiled are never used at all.

The acronyms and abbreviations used in teen texting: Are they laziness, or are kids just in too much of a rush these days to spell whole words?

The last thing texting could possibly be is lazy. It’s actually quite effortful to text, especially on the early mobiles where the arrangement of the keypad was never designed for texting. Abbreviations were a way of reducing the amount of effort involved (and, sometimes, cost, in early methods of paying), so we’re talking ergonomics here. But the main linguistic reason for abbreviating (whether in texting or elsewhere) is not ergonomic but sociolinguistic. There’s an old jingle: ‘The chief use of slang, is to show that you’re one of the gang’. And abbreviations take their place alongside slang as one of the ways in which you show you belong to a group. You use the same abbreviations as your mates do – whether your mates are doctors, lawyers, journalists – or texters. Another interesting research finding shows this in the form of texting communities – that is, groups of people who text in similar ways. Texting dialects, if you like. You see them on Twitter too.

Texting acronyms and abbreviations seems to have become a pop culture phenomenon. You can find T-shirts emblazoned with text phrases and everyone from teenagers to politicians have incorporated their use into their spoken vocabularies. Why were text messaging phrases able to catch on and become so popular so quickly?

Yes, and when we did the Evolving Exhibition at the British Library, they had texting badges for sale, which shows how linguistic succinctness readily translates into commercial realities. They were novel, fashionable – in a word, ‘cool.’ And we all want to be cool.

But all this is really now a bit out of date. You say ‘have incorporated their use’ into speech. Really? Give me some examples. You will say ‘LOL’. Agreed. Now give me another. You will say ‘OMG’. And another…? You will quickly run out of steam. The fact is that hardly any abbreviations have entered the general spoken mainstream. Only a couple have been picked up by the dictionaries, and the question of how long they will stay there is unclear – as textisms seem to be on their way out.

As I say, I often go into schools and talk about texting with the students. The other week I visited one school and I looked at the texts of a group of sixth-formers (16-17-year-olds). No abbreviations at all. I asked why not. The kids said they didn’t use them any more. They weren’t cool. They were naff. ‘We used to use them when we were younger’, said one. And the clincher: one guy says to me ‘I stopped using them when I realised my parents were’. I don’t know how widespread this is, but it’s a sign of the times.

– – –

To learn more from David Crystal visit his website or purchase his book here.

Liz Faris, Associate

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments