Have you ever left your doctor’s office feeling confused after a visit? Perhaps the doctor’s explanation of your diagnosis or recommended course of treatment went right over your head? You are not alone. Unfortunately many people don’t understand everything their doctor explains to them and too often people don’t speak up to let their doctor know this. This month, as we explore slang, jargon and acronyms, we wanted to tackle one of the most widespread and confusing types of jargon: medical jargon.

This week Collaborative Services spoke to Dr. Richard Senelick about the importance of interpreting medical jargon. Senelick is a neurologist specializing in neurorehabilitation, the medical director at HealthSouth RIOSA, a lecturer, and an author who has contributed to the Huffington Post, The Atlantic, AOL Healthy Living, and WebMD. Dr. Senelick has written on the use of medical jargon and offers advice on what patients can do to improve their health literacy.

We spoke with Dr. Senelick about the use of medical jargon, his ideas for teaching medical professionals to be better communicators and what patients can do if they find themselves not fully understanding an explanation from their doctor. We welcome his insights.

– – –

You’ve written that jargon can be pervasive in all professions, but it may have the biggest impact when it occurs between doctors and patients. Why?

Every profession has its own special language, but medicine seems to have more than its share. I always tell people that “if you knew the meaning of all the big words I couldn’t make a living.” From an educational standpoint, medical professionals have no choice but to learn the complicated names that come along with anatomy, physiology, chemistry and medications. If you are going to learn the names of all of the muscles in the body, you must learn their formal names so that you can communicate in a precise way with your colleagues and the rest of the medical world. The same is true with the long list of medications. I can’t just go to the hospital chart and order “that small round yellow pill for blood pressure.” I think the problem is that the field of medicine has so many words and terms that are not known to the general public and that medical professionals are never taught how to communicate effectively with their patients. It is like going to a foreign country and not speaking the language. The medical professional needs to learn to speak in a manner that their patient and other professionals understand. It is not just patients. Physicians may speak to nurses in terms they do not understand, but the nurse is too embarrassed to say they do not understand. It is a medical disaster waiting to happen.

Medical jargon is one of the most commonly used misunderstood types of jargon. What is it about medical jargon that makes it difficult to be broken down into terms everyone can understand?

I don’t think it is that difficult to fix, once you understand that you are the problem and learn how to communicate effectively. There was a widely read satirical comic strip, Pogo, who’s main character was a philosophical possum who famously remarked in 1953, “We have met the enemy and he is us.” We just don’t make enough of an effort or teach our students how to be more effective in their interactions with their patients. I suspect there is also a sense of “self importance.” Physicians may want to show us how smart they are. It reminds me of a parent telling their child to, “use your big words.” I know a physician who speaks with so much jargon that half the time I don’t have a clue what he is saying. I wonder if he knows.

I suspect that most health care professionals don’t realize how much they need to simplify their language. The government’s Health Literacy Fact Sheet points out that nine out of 10 individuals lack the health literacy skills to manage their health and prevent disease. The average doctor may tell their patients, “Your hypertension is negatively impacting your cardiac risk factors and puts you at a higher risk for a cerebrovascular event.” For the doctor, these are simple words, but they have no idea that their words fell on deaf ears. How hard would it be for the doctor to say, “If we don’t do a better job of getting your blood pressure down, it is going to hurt your heart and you may have a stroke?” Now I have their attention. The average American reads at about the 6th or 7th grade level. The problem is how do I measure the way I speak or write so it matches that standard. Unless someone tells me, either in school or later in my career, how would I know where to “place the bar?”

In an April 2012 blog you wrote for the Huffington Post’s Healthy Living section you describe your own experience having trouble interpreting a doctor’s medical jargon during a visit with your wife. You are a neurologist and author and yet said that you didn’t have a clue what the doctor was talking about. You called yourself the “poster boy” for inadequate “health literacy.” What is “health literacy?”

I used a quote in my blog, “Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and devices needed to make appropriate health decisions” Wow, do you understand that? That is the government’s Fact Sheet definition. I think they just broke their own rule. How about, health literacy is the basic information that a person must obtain in order to understand the medical people they meet and then be able to take care of their own health and make the right decisions? It is kind of embarrassing that we can’t even use the proper language to explain the problem.

Is there a relationship between inadequate health literacy and poor overall health?

There is no question that people with poor health literacy don’t do as well as those people who have a clear understanding of what their doctors and nurses are telling them. I also wrote a blog on the “Healing Power of Story Telling” that referred to a study where people with high blood pressure who received their information from other people with high blood pressure had better outcomes. Those people knew how to explain the information in terms the people could understand.

In addition people with low health literacy:

- Use more medical services to treat their disease than to prevent it. In other words they may take more pills to treat their high blood pressure instead of using other methods that would lead to a healthy lifestyle.

- End up in the hospital and emergency room more often because they do not have the knowledge to manage their disease.

In fact an article in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) noted that “poor health literacy is a stronger predictor of a person’s health than age, income, employment status, educational level, and race.” That is powerful statement. As a country we cannot afford to remain illiterate about our health.

In the same Huffington Post blog you state that the use of jargon begins in medical school. What do you think medical schools can incorporate into their curriculum to help medical professionals learn to communicate more effectively and become as you state “medically bilingual?”

First, we need to teach the teacher. How many times do you hear someone, including doctors and lawyers, say “She and me went to movies together last night?” It’s like hearing fingernails on a blackboard, but these “educated” people don’t realize they are using poor grammar. Somewhere along their educational path no one took the time to correct them. So, once we have the medical educators on board, they can stop their students when they are speaking to their patients in jargon. Role playing sessions and practice can go a long way in this regard. I stop students, nurses and therapists in their tracks and ask them, “how could you say that so that anyone would understand?” My “Gramps” was one of my heroes- 30 years after his death, he is still is. He came from Poland in steerage class, unable to read or write. I ask myself,” How would I explain this to Gramps so he would understand?” There is so much that a medical student needs to learn that no one is going to create a formal course on jargon, but it can take place at the bedside. But, first the role models (teachers) need to get it right. No more “She and me’s!!”

Why are people so afraid to speak up and let their doctor know they don’t understand the jargon they are using?

Most patients are intimidated by the doctor-patient relationship. When I read the comments to my blogs in the Huffington Post and The Atlantic, I am impressed by the anger and frustration people have towards their doctors and the health care system. Many people are afraid that if they are too strenuous in their questioning of their doctor, they will make them angry and negatively impact their relationship. A good friend of ours who lives elsewhere just had surgery. My wife went there to be an advocate for her and it made a big difference. She was a second set of ears and was able to ask the questions our friend could not.

If you do not understand what your doctor is saying, immediately stop them and ask them to use simpler language. Don’t pretend that you understand when you do not. Here: are some more tips

- Be assertive, but friendly. Let them know if you still have questions.

- Tell the doctor what you think they said to be certain that you understood them. This is called a “teach back.” ( see below)

- If you feel you need more time, ask to schedule another visit in the near future.

- If the doctor is very busy, ask if there is a nurse or assistant who can answer your questions.

- Take a friend with for another set of ears and always take notes.

- Ask who you can call if you still have questions when you get home.

What is the “Ask Me 3” program and what makes it effective in cutting through medical jargon?

“Ask Me 3,” is a terrific program that encourages patients to ask three basic questions to improve communication between themselves and the people caring for them. The three questions you need to ask your doctor or nurse are:

- What is my main problem?

- What do I need to do?

- Why is it important for me to do this?

This program is directed toward helping people understand the instructions that their health care team is giving them. As I noted in my article on medical jargon, my wife and I have walked away from a doctor’s visit and asked each other, “what did he say?” The problem with “Ask Me 3,” is that it only works if the health care professional speaks in terms the person understands. If the doctor uses jargon, it will not matter what three questions the patient asks or how many times they ask it.

You often hear about nurses helping interpret medical jargon to patients. Why is this is becoming a larger part of their role?

I am not as optimistic as you are that nurses are stepping in as effective translators. I underwent hernia surgery three months ago. It was an uneventful day surgery, but when it was time to go home, the nurse handed me a stack of pre-printed instructions for a patient with a heart condition! I just wrote an article for The Atlantic on “Teaching Doctors How to Think.” People are getting better at asking questions, but they need to get better at telling doctors and nurses that they do not understand them. I think nurses, aides and therapists need as much education as the doctors. They are just as guilty as the doctors. It is a system wide problem. I think this is why you see all the programs like “Ask Me 3” that are aimed at educating the patients.

As a neurologist, do you find yourself slipping into jargon when explaining something to a patient? What tips do you use to remind yourself not to use jargon when you find this happening?

I lecture and write a good deal. That has helped me with my patient interactions, since I am constantly going back to my rule,” Would my Gramps understand me?” Here are some simple rules for all health care professionals to follow:

- Repeat essential information. It is called the “Teach Back Method.” Patients forget 80% of what they are told and 50% of what they retain is incorrect. We shouldn’t ask, “Do you understand?” Teach Back instructs us to ask, “ I want to make sure I explained things well so please tell me in your own words what is wrong with you, how will you take your medications, etc.”

- Use plain language. Constantly ask yourself, “did I say it without using technical words?” A big part of the problem is that doctors do not think words like hemorrhage, biopsy, rectal, and tissue are jargon words. Remember, “What would Gramps think?”

- Consider cultural and socioeconomic status. We are a diverse community of immigrants and many of our patients are bringing an entirely different set of ears to the conversation.

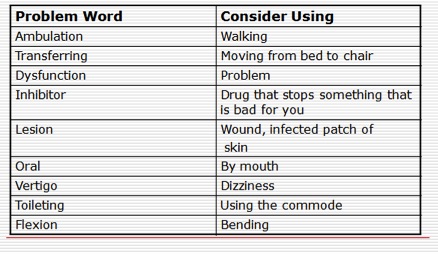

Here are Some Examples

( From one of my lectures)

– – –

To learn more about health literacy visit these resources:

U.S. Department of health and Human Services- Quick Guide to Health Literacy

Joint Commission- “What did the doctor say?: Improving Health Literacy to Protect Patient Safety

NIH Introduction to Plain Language

Health Literacy: National Network of Libraries of Medicine

To learn more from Dr. Richard Senelick you can purchase his books and DVDs here.

Liz Faris, Associate

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments