There is an intelligent creature that lurks among us and preys on words. In its natural habitat it surrounds itself with dictionaries, thesauri, writing instruments, and word-processing programs. This elusive creature, known as the verbivore, is a master of language arts and can seemingly craft catchy, creative, and thought provoking-phrases at the blink of an eye. Its existence can be traced back to the beginning of human kind, when the first words were uttered, but only the alpha of this species has gone on to succeed in society.

This month, Collaborative Services has tracked down a verbivore right here in San Diego and we spoke to him about his love of language. Admitted verbivore Dr. Richard Lederer is a best-selling author, columnist, former radio show host, and current radio show contributor. He has appeared on nationally broadcast television shows, including NBC’s Today Show and CNN Prime Time, and has been elected International Punster of the Year and won the Toastmasters International’s Golden Gavel. Currently, Lederer has a weekly column, “Lederer on Language,” which appears every Saturday in the San Diego U-T and also has American history quizzes every day therein. You can say this verbivore has a way with words.

As we continue our theme on words this month we wanted to hear from a leading linguist about his thoughts on the subject. Lederer took some time to share with Collaborative Services his love of words, his thoughts on the evolution of language online, and how growing older gracefully has helped him become more wordstruck. We welcome his insights.

– – –

You’ve written more than thirty books on the joys of language. You seem to love not only how words sound and what they mean, but how you make puzzles out of them, like anagrams, palindromes, and crosswords. When did this love of words start, and when did you first think to write about words themselves, rather than the sentences or stories they create?

I can’t remember when I wasn’t a wordstruck, word besotted, word bethumped wordaholic. Early in my life I observed that a butterfly will flutter by, creating my first spoonerism, even though, at the time, I didn’t know that eponymous word. Decades later, I graduated to the more sophisticated reversal “A dragonfly will drink its flagon dry.”

Over time, I became fascinated with words themselves, not just their content. Carnivores eat flesh and meat; piscivores eat fish; herbivores consume plants and vegetables; verbivores devour words. I am such a creature. My whole life I have feasted on words — ogled their appetizing shapes, colors, and textures; swished them around in my mouth; lingered over their many tastes; felt their juices run down my chin. We have achieved our level of civilization because human beings are rather different from each other. Somehow I got born a verbivore, and I do my best to contribute that gift to the mix.

What made you want to create the public radio program “A Way with Words”? To what do you attribute its success?

Language is like the air we breathe: It’s invisible, it’s all around us, we can’t get along without it, yet we take it for granted. But when you step back and listen to the sounds that escape from people’s mouths and luminesce up on their computer screens, you are in for a lifetime of joy in a world in which you drive in a parkway and park in a driveway – and your nose can run and your feet can smell.

Language is the defining characteristic of our humanness. Not only do we human beings define language. We are language. What topic, then, could be more entertaining, enlightening, and edifying than words? Add to that the presence of hosts like Charles Harrington Elster, my original partner, and our successors, Martha Barnette and Grant Barrett, each of whom have put in more than the Malcolm Gladwell 10,000 hours of focused practice on our passion for words, and you have the perfect ingredients for a widely-listened-to show.

Current hosts of A Way with Words, Grant Barrett and Martha Barnette. A Way with Words first aired in 1998 with co-hosts Richard Lederer and

Charles Harrington Elster.

(Credit: Last.fm)

You’ve spoken about the “miracle of language,” and you’ve studied words in other languages besides English. What are some key differences between English and the other languages you’ve studied, both in their origins, and how they convey meaning?

The history of English (“Angle-ish”) bequeaths us a unique three-tiered tongue. The common words of everyday life, many of them fashioned from a single syllable, Anglo-Saxon is the foundation of our language. Its directness, brevity, and plainness make us feel more deeply and see things about us more truly. The grandeur, sonority, and courtliness of the French elements lift us to another, and more literary, level of expression. At the third tier, the precision and learnedness of our Greek and Latin vocabulary arouse our minds to more complex thinking and the making of fine distinctions. Each of us English speakers re-enacts the history of our language as we grow up. We acquire the Anglo-Saxon words so early that we can scarcely remember learning them. As we become adults, we learn the harder, more learned words, which generally derive from French, Greek, and Latin.

What most immediately sets English apart from other languages is the richness of its vocabulary. More than 600,000 words repose in our biggest, fattest dictionaries, and the true size of our lexicon exceeds a million words. In comparison, German, according to traditional estimates, has a vocabulary of about 185,000, Russian 130,000, and French and Spanish around 100,000.

One reason English has accumulated such a vast word hoard is that it is the most hospitable and democratic language that has ever existed. English has never rejected a word because of its race, creed, or national origin. Having welcomed into its vocabulary words from more than three hundred other languages, ancient and modern, far and near, English is unique in the number and variety of its borrowed words. Fewer than thirty percent of our words spring from the original Anglo-Saxon word stock; the rest are imported. As the poet Carl Sandburg once said, “The English language hasn’t got where it is by being pure.”

Sir Philip Sidney, the quintessential Elizabethan — at once poet, courtier, and soldier — celebrated this word-wealth: “But for the uttering sweetly and properly the conceite of the minde, which is the ende of thought, English hath it equally with any other tongue in the world.” Sidney saw how the abundance of synonyms and near synonyms in our language offers wondrous possibilities for the precise and complete expression of diverse shadings of meaning.

A portrait of Elizabethan poet Sir Philip Sidney painted by the younger John Decritz.

(Credit: https://humphrysfamilytree.com)

You’ve written books for both children and adults. How do you write differently for each audience?

I’m astonished to find that about 20 percent of my current titles are books for children. A writer must discover what kind of writer he or she is, and long ago I realized that I could never be a writer of fiction. That’s because I stink at creating fictional elements such as plot, character, motivation, setting, and dialogue. But I love explaining ideas and gradually found that I could share language fun and skill with hormones poured into sneakers, that is, children ages eight to thirteen years. That’s a market sadly neglected, in part because parents often stop taking their children to book stores around the third grade.

I very much respect the intelligence of children, so my subject matter for boys and girls is not much different from what I write about for adults. But my work for kids is cast in a simpler sentence style and includes more games and illustrations.

The Internet has created a whole new dialect of abbreviations and memes. As a proud septuagenarian (Lederer turns 75 on May 26) who has studied words for some time, what do you make of so-called “LOL-speak”? Are you enjoying how language is evolving online?

Long ago, Heraclitus taught us that we never step in the same river twice. Similarly, we never step in the same language twice because, even as we do, the river rushes ahead. Lexically, the English language gains about three words each day, and think about how established words acquire new means. Think about the computer’s impact on words such as back up, bit, boot, hack, memory, menu, mouse, park, prompt, port, scroll, spam, trash, virus, window, and worm.

As a linguist, one who studies language scientifically, I am bullish language evolution, including emailing and texting. Early Victorians wrote scads of personal letters to each other, but the invention of the telephone significantly diminished that number. Nowadays, cyberspace is filled with more personal letters than we’ve had for almost a century and a half. And the new cyber language makes for an exciting exercise in concision, as long as writers understand that numbers in place of prepositions and other such shortcuts are not appropriate in formal writing. Being good in language involves the ability to code-switch from one context to another.

You’ve written several columns lately about poetry. What interests you about poetry? How is it different than prose? Do you think most people misunderstand it?

Sadly, there are scarcely more people reading poetry than there are writing poetry these days. Most of us view/hear poetry as an artificial refinement of natural speech or an unrhymed and incomprehensible language. But in the literature of every country poetry comes before prose. “Poetry is the eldest sister of all arts, and parent to most,” according to the playwright William Congreve. It is the oldest language we have – the most primitive, the most elemental, and the most natural expression of ourselves as human beings. Poet John Frederick Nims has said that “poetry is the way it is because we are the way we are.”

You’re a prolific writer. Does your vast knowledge or words give you more to say, or is it just that you love the topic so much?

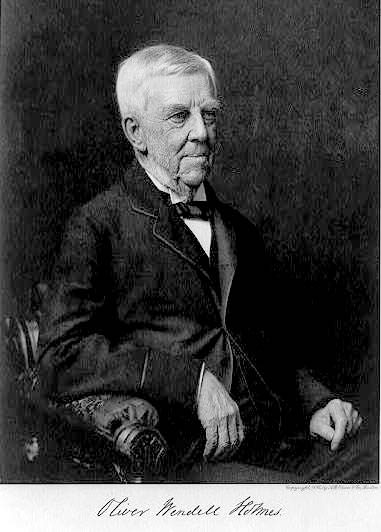

Both. Because, in the words of Oliver Wendell Holmes, “Language is the skin of living thought,” a passion for words and breadth and power of one’s vocabulary gift you with more to say. Simultaneously, when a passion for words reaches deep into the heart’s core, you are incandesced to share what you know.

I’ve devoted my life to blowing up the distance between who I am and what I do. The more I have become one with what I do and the more I do what I am, the more easily flow the words about words. I’ve been choosing words and cobbling sentences for more than six decades, and I’d like to think that I still learning how to do that better each time.

You’ve written about growing older and trying to do so gracefully. How has aging influenced your love and respect for words? How has that love helped you express your feelings on aging?

To purloin a few lines from William Shakespeare, my life has become the sere, the yellow leaf that falls from the bare, ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang. I like being seventy-five; it’s such a lovely change from being young.

As time’s wingéd chariot hurries near, as the body fades and loved ones depart the earthly stage, words and language endure and indeed prevail. I have never been more wordstruck, besotted, and bethumped, than I am right now. Now that I am full of years and the evening star is in the sky, I find myself shot through with gratitude that I have been able to labor so long and so lovingly in the language vineyards. I have actually made a decent living as an English major. Yippee! Huzzah! Woo–hoo! What a ride!

– – –

Are you looking to find your own way with words? Pick up a copy of one of Lederer’s books as a start and then jump right in to the wonderful world of words. To learn more about Lederer visit www.verbivore.com.

Liz Faris, Associate

Collaborative Services

Recent Comments