Arguably the most profound effect that social media has had is this – it has changed media from sending information out into sending information back and forth between customers, citizens and the media. Restaurants can’t advertise on Yelp! without risking the wrath of a disgruntled customer. Celebrities can’t plug their new comic book movie without fans on Twitter demanding to know why the hero’s hair color has changed. Reporters know when they publish a story, their research is subject to scrutiny in the comments section.

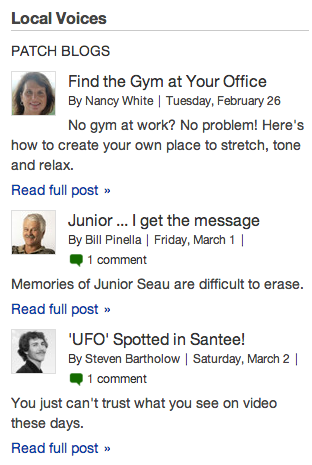

Some companies have been wary of the back and forth that social media generates. But for Patch.com, it’s part of their DNA. The network of hyper local news websites relies heavily on user-generated content like photos, blogs and breaking news updates.

In 2007, disappointed in the lack of online news about his neighborhood in Greenwich, Connecticut, then Google executive Tim Armstrong teamed up with his colleague Jon Brod and media veteran Warren Webster to create Patch Media. The team generated an innovative business model in which all editors and some contributors are trained journalists, but much of the content comes from engaged residents who are invested in local issues.

Now, more than 1,000 communities have a Patch.com site. Whether it’s a school committee decision, a power outage from a storm, or your neighbor’s tips on gardening, Patch aims to capture the spirit of a community from the ground up. So much so that its news is termed “hyper local.”

The Collaborative Services blog spoke with Patch co-founder Warren Webster about how his company is expanding in an age when most news organizations are contracting, and how social media has made their business model possible.

In recognition of the rise of social media, Time Magazine named “YOU” the person of the year in 2006. (Credit: Time Magazine)

1. You began your career in the print newspaper and magazine world. In what ways is a Patch site like a traditional newspaper’s website, and how is it different?

Our goal from the beginning of Patch has been to add something new and needed to a community, not just to recreate the local newspaper. Patch offers residents the most important news stories and events, which is similar to what a newspaper site does, except that our news and events are a blend of our own original reporting, contributed content from residents, and curated news collected from other sources. A newspaper tends to be a one-way conversation: Reporter to reader. Patch is a community platform where there are many opportunities for conversation: resident to resident, business to resident, resident to Patch, etc. Patch is also different because it is real-time, 24/7, and if something important is happening in a Patch neighborhood – storms, power outages, school closings, for example – you’ll know about it immediately. Our mobile sites and emails are among the most popular ways people use Patch, so you might even say that we’re not simply a website.

2. What is the significance of the name “Patch”?

The name Patch represents your home turf, your patch of land, the place where you live. Plus it’s kind of fun, and that’s an important element of our brand.

3. How does Patch use social media in its reporting, marketing, and reader engagement?

Social media is intertwined throughout Patch. For example, each Patch site has a Facebook page and a Twitter feed, and these are substantial sources of traffic. We use social media to promote our best content and things like contests and polls. To us, social media is just another way for people to interact with Patch, in addition to the site, mobile, email, and so on.

4. Are there local issues you think Patch sites are better suited to cover than traditional news media, including local community newspapers?

I believe Patch has done some of its best work when something is happening fast, in real time, because we can react extremely quickly to keep people informed. This happens every day on Patch, but one notable example is Hurricane Sandy. More than 300 of our Patch communities were affected by the storm, and we had over 450 Patch editors and contributors covering it. Our staff posted over 12,000 storm-related articles, including essential power, traffic and shelter updates on the site, on mobile, and through social media. Residents themselves added over 50,000 comments and updates, and over 5,000 photos. When power is out, Patch is still on, and we saw a 300% increase in mobile traffic and a 700% increase in mobile app downloads that week. Patch is truly a lifeline.

Patch.com helped East Coasters share what was happening to their communities even when the power went out during Hurricane Sandy last October. (Credit: The New York Times)

5. When it comes to getting the word out about local events and issues, what methods has Patch found the most effective?

One of the great things about Patch is that people can interact with it however is most convenient for them. Some people think of Patch as local email updates, while others use the site. I think it’s the combination that is most effective.

6. To what extent does social media engagement drive what you cover? If certain stories are getting more comments or Tweets, are more resources put into it?

We definitely monitor closely what might be a hot topic on social media sites, and our editors are actively engaged in conversation with residents on these sites, so I would say yes, it definitely drives coverage to some extent.

7. Many Patch contributors are local residents who are invested in their community, but may or may not be trained as reporters. Do you think this was possible before social media?

Most, if not all of our local editors are either experienced journalists or journalism school graduates, or both. But I would say that their ability to navigate the world of social media is a critical and necessary skill for our staff. Contributors who are not full-time Patch staffers (such as bloggers, for example) might not have the same journalism credentials but bring a fantastic variety of voices and expertise to the sites.

8. What are the incentives to using residents as content providers? Are there any challenges?

Our local editors and the regional editors who manage them are all paid, full-time employees. In addition to their original reporting we actively encourage contributions from residents in the form of bloggers, or simply allowing people to upload events, photos, videos, and other types of content directly to the site. When we built in the blogging system, we were amazed by how quickly it was adopted. We now have over 35,000 bloggers signed up. There are many people in every community who value the opportunity to share their thoughts, ideas or expertise on things with a wider audience, and that is the primary incentive. That said, we are always working to remind and encourage people to contribute more often, as it makes the sites more vibrant and active.

9. News organizations have historically had a difficult time convincing advertisers that ad space on a website is just as valuable as in print. How does Patch attract advertisers? How do you convince perspective ad buyers that online and mobile ads are valuable? Does social media play a role?

News organizations made a mistake early on, in my opinion, by devaluing their online offerings, giving them away in many cases as added-value or bundling them with print. So it has been an uphill climb for them to drive up the value of their online display ads over time. For us, it really comes down to one thing: ROI for the advertiser. If we can show a business owner that advertising online will drive offline, local behavior — visiting a store, buying something, attending an event, whatever action they are looking to inspire — we will have a customer for life who is willing to pay to be on Patch. And we’re seeing significant success. Our ad revenue more than doubled and is on a great trajectory so far in 2013.

10. How does your company decide when to give a town its own Patch? Is it based on population, engagement, something else?

Ultimately we feel like every community needs Patch. When we first built Patch back in 2008, we knew we could launch anywhere. As a start-up, still privately funded, we wanted to be very smart about where we went first. So we looked at the elements of a community that would likely make us most successful as quickly as possible. It was both an art and a science. We built a 52 point algorithm weighing factors like household income, retail spend in the town, density of businesses, ranking of the local public high school (a strong school system likely has a very engaged group of parents supporting it), voter turn out and population. We ran every census tract in America — all 66,000 — through the algorithm, plotted them on a map, looked for clusters (important for the way we manage the sites) and that gave us a list to start with. Our first three towns, launched in February, 2009, were Maplewood, South Orange, and Millburn-Short Hills, NJ. And now we have over 900 in 22 states.

Elizabeth Malloy, Associate

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments