Most of us would be honored just to win an award; Philip Meyer has one named after him. This month, with our blog’s focus on the 4th Estate, we’ve set out to meet today’s press, and few people can give us a better introduction than Meyer. A lifelong newspaperman going back to his childhood job as a paper carrier, Meyer has worked as a reporter at the Miami Herald, Akron Beacon Journal and Detroit Free Press. He became a professor in the early 1980s and taught journalism at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retiring from teaching in 2008, Meyer has since focused on writing and self-publishing a memoir, Paper Route: Finding My Way to Precision Journalism.

A veteran of the 4th Estate, Meyer has become renowned for his books about the demise of the very medium that gave him his career. When his book The Vanishing Newspaper indicated newspapers would be gone by 2043, many reviews and articles took that date and ran with it, something Meyer says he didn’t necessarily intend.

Don’t count Meyer among the ink-stained hand-wringers who mourn the loss of the broadsheet though. For one thing, he has embraced new technology. The octogenarian has his own blog, and calls himself an “Apple convert.” Meyer was never afraid of computers. He is considered a pioneer of computer-assisted reporting, the industry term for analyzing databases to find trends and stories. He helped the Free Press win a Pulitzer Prize when he used survey research to show that people of various socio-economic status all participated in the 1967 Detroit riots.

Plus, Meyer does not believe newspapers will ever entirely disappear, at least not in our lifetime. The medium will likely become more niche, as other technologies have before it, but there will always be some market for the tangible, permanent printed word. In 2008, when Barack Obama became the first African American elected president, retailers who usually still had papers left at closing time, found themselves sold out before the end of the morning commute. Customers wanted something to commemorate the historic event, and you can’t pass a Washington Post app down to your grandchildren.

As we continue to explore the 4th Estate this month the Collaborative Services blog spoke with Meyer about his predictions for the newspaper industry, what he believes it could have done to save itself, and what it must do to stay relevant in the future.

– – –

You began your journalism career as a newspaper carrier for the Clay Center Dispatch in Kansas in 1943. The newspaper industry has changed quite a bit since then. What do you believe has been the most significant change the industry has faced and why?

That’s easy: disruption of its business model by successive waves of technology. Newspapers peaked around 1920, when 130 papers were sold for every 100 households. Then other media, starting with radio, began taking business away. That process accelerated when Google and Craig Newmark discovered in the 1990s that the Internet was a highly efficient advertising medium. Newspapers coped through most of the 20th century by consolidating down to one paper in most markets and using monopoly power to control prices. They can no longer do that.

In your 2004 book the Vanishing Newspaper you offer the newspaper industry a business model to outlast the technology-driven changes it has faced in recent years. How did you come to the conclusion that this model could save the industry?

As one reviewer said, it was a hail-Mary pass. At Knight Ridder, we recognized that our main product was influence, and that quality journalism was needed to maintain that influence. But most of the industry was adopting a harvesting model: raise prices, cut quality, and extract as much money as possible before the business dies. I thought that empirical verification of the influence model would make owners and managers reconsider that. But I was too late.

What type of response have you received from the newspaper industry regarding your recommended model?

There was interest, as evidenced by book sales and speaking invitations. But a mature industry just doesn’t have the heart to take risks. Any new model in this technological environment is a risky business. Harvesting is not an irrational strategy, and it clears the field for new kinds of ventures.

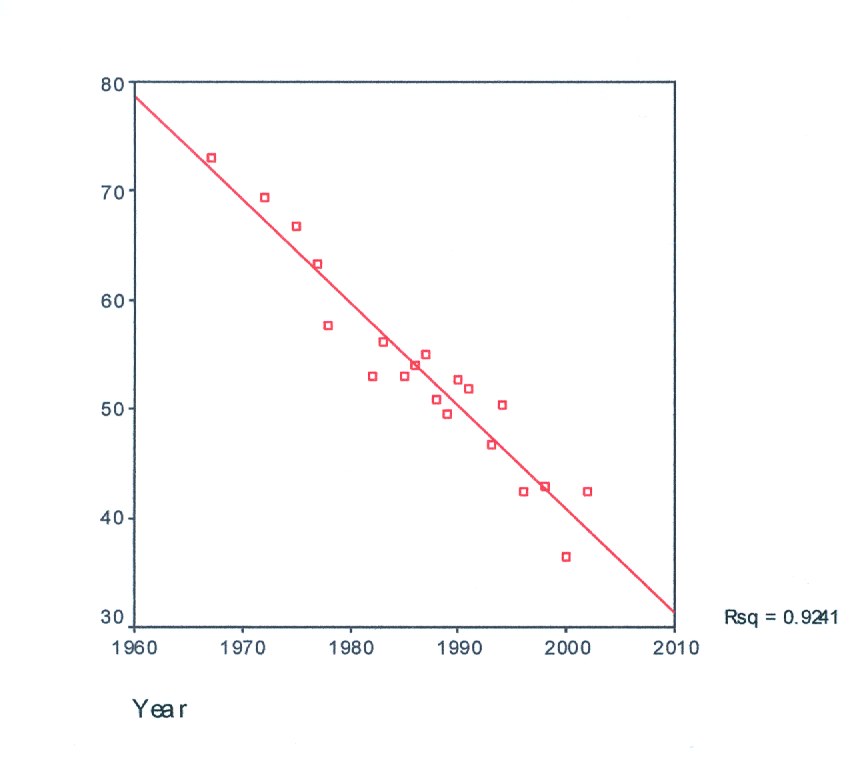

Among the charts you used in The Vanishing Newspaper a particular one gained a lot of interest. This chart showed the decline of newspaper’s daily readership by adults starting in 1967. As the regression line continued it reached zero in 2043. Many people took this as a prediction of when the last issue of the last newspaper will occur. You have since clarified many times that this is not a prediction. Why do you think so many people misinterpreted this?

“Newspapers are gonna die in 2043” would fit on a bumper sticker and is therefore easy to remember. I should have done a better job of explaining why nature doesn’t like straight-line trends.

The statistical graphic used in The Vanishing Newspaper showing the percentage of adults who told the National Opinion Research Center that they read a newspaper

“every day.”

(Credit: Philip Meyer, The Vanishing Newspaper)

Do you also think that this large-scale misinterpretation may be a reflection of today’s media culture? News sources strive to be the first to break a story, which can sometimes cause important details to be lost in the hustle.

Now that is a researchable question! If I still had graduate students, I would suggest finding ways to test two conflicting propositions: 1. A lie spreads so fast that truth can never catch up (as Mark Twain suggested) and 2. The high velocity of information greatly reduces the half-life of misinformation because everyone has access to everything, and truth is stronger than falsehood (as John Milton suggested). Let’s put those two ideas to a test in a fair and free encounter. We could start with a few good case studies and maybe invent some laboratory experiments.

You also have a blog and your most recent post offered yet another opportunity to clarify this misinterpreted prediction. In this post you say that you are sure that newspapers will still be publishing in the year 2043. Why are you so sure of this?

As Donald Shaw observed in a lecture at Indiana University, old media technologies tend to survive by finding specialized niches. When TV arrived, radio shifted from being a mass medium to serving a collection of specialized audiences. Print is doing the same in response to the Internet. We can already see how community newspapers, a basic specialization, are remaining relatively robust. Of course, if you are going to bet on this, you had better include some specification of what you mean by “newspaper.” My guess is that in 2043, you will still be able to line a bird cage with it.

With the rise and accessibility of technology we are also seeing a decline in investigative reporters. Why should the public be concerned with this loss?

There will always be a market for investigative reporting. We’ll just have to discover new ways of paying for it. Non-profits are starting to pick up some of the slack. We might regress to the early 19th century model of journalism supported by narrow political and business groups. I see a rough period of trial and error with strange new forms emerging. Maybe investigative bloggers will save the day.

What can journalists and individuals do to adapt and survive in such a rapidly changing industry?

Stay interested. Pursue a liberal arts education. It will help you develop the courage and the imagination to try new things. The benefit of a changing industry is that you can become part of the change. If you don’t like risk, you shouldn’t be in journalism anyway.

You have had the great honor of having an award named after you. The Investigative Reporters and Editors, Inc. Philip Meyer Award recognizes the best journalism done using social science research methods. Have you had the opportunity to be involved in the recipient selection process or to meet any of the recipients?

I have met some of the recipients and been very impressed by their work, but I have not been part of the selection process, nor do I aspire to be. The tools and techniques are changing very fast, and my role at this stage should be more like a cheerleader than a player.

If you had a crystal ball that you could use to look into the future to 2043 what do you think the newspaper industry will look like then?

It will be absorbed into multimedia enterprises employing a variety of ways to collect and distribute knowledge. Some of those ways of distribution will use ink on paper made from dead trees. Community newspapers will still be strong. But there will be many strange, even weird, experiments. Knowing that, I try never to criticize any bizarre new way of doing journalism. Why? Because no matter how crazy an innovation sounds, I cannot be certain that it will not work.

– – –

Thank you Mr. Meyer for sharing your thoughts and research on the newspaper industry and for letting us turn the tables and interview you after a long and illustrious career interviewing others. To learn more about Philip Meyer and his work visit his blog here.

Liz Faris, Associate

Collaborative Services, Inc.

Recent Comments